[SPOILER ALERT: SOME PLOT POINTS REVEALED]

[SPOILER ALERT: SOME PLOT POINTS REVEALED]

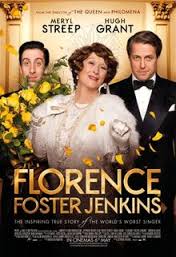

For readers who are unfamiliar with this series, “Shrink at the Movies” is a not-very-consistent string of essays (ponderings, I like to call them) from my point of view as both a licensed psychotherapist in California (Licensed Clinical Social Worker, or LCSW) and as a life-long movie fan. Being a therapist in Los Angeles inevitably means having many clients somehow involved in the film/television entertainment industry, and so my work in therapy is forever colored by the setting of “Hollywood,” both geographically and conceptually. While the spirit moves me only occasionally to write about movies from a mental health professional’s point of view, there are times when a movie inspires existential and humanitarian consideration. The latest, “Florence Foster Jenkins” (2016) is one of these.

Watching Meryl Streep act in anything is always a treat, not only because of her chameleon-like talent for inhabiting a character, but also because she seems to radiate a certain joy in her work where she looks like she’s having the best time. Such is the case in her playing the titular role in the biopic on “Florence Foster Jenkins”, the 1940’s New York socialite and arts patron who loved music so much that she fancied herself a classical singer and pursued giving concerts, with only one small flaw: she couldn’t carry a tune in a paper bag.

I first learned about FFJ (as I will call her for short) from a friend who was with me in the Gay Men’s Chorus of Los Angeles (GMCLA) in the 1990’s. He played me parts of her album (yes, she made one) that was hysterically funny to listen to because of its sheer ear-splitting butchering of these classical oratorios. Since then, I’ve seen a Broadway play called “Souvenir”, starring Judy Kaye, which was about the relationship between FFJ and her accompanist, Cosme McMoon. That play was so moving at the end, because after two hours of hearing this comically-bad singing (the genius of Kaye), we get to hear how Florence “heard herself” in her own head, flawlessly sung again by Kaye (Meryl Streep does the same schtick in the finale of the movie).

Of course, in my own “Shrink at the Movies” kind of way, it got me thinking about the lessons and implications of the story for all of us. Essentially, FFJ embodies a story about someone who is really quite delusional – and grandiose, believing that she has a talent that, by all accounts, she simply does not have. Probably all of us, at one time at least, have the anxiety about something that we are going to be “found out” and that our accomplishments or talents aren’t that great shakes at all. This is the kind of stuff that gives us all performance anxiety in so many different situations, from giving a speech, to a sales presentation, to a job performance review, to hiring/firing, and of course anytime we have to present supposed examples of our “talents” (singing, acting, modeling, drawing, designing, writing, composing, selling, etc.) to someone else.

FFJ presents a fun premise in that while many (most) of us have some kind of performance anxiety (often!), we tend to do pretty well and our insecurities and worries are usually for naught. We get the jitters, we “perform”, we do just fine, we get kudos, and we make it all “look easy” to everyone else, but what if we really ARE just plain BAD? What then? The movie of “FFJ” and its predecessors dare to ask this. It’s a lesson in heart, and chutzpah.

Anyone might be nervous singing at Carnegie Hall (I was when I performed there as part of the Gay Men’s Chorus of Los Angeles, in 1994, and it was really fun!) but it takes real guts to go out there in that esteemed place (as FFJ did in 1944), especially when one has zero talent. And maybe that’s the lesson of “FFJ”, that perhaps guts and gusto to just go out there and sing your heart out, regardless of quality, is a certain lesson in life that while we don’t have to be perfect at what we do, we do need the guts to just do it. As one of my own previous therapists once said, “If something is worth doing, it’s worth doing badly.” Don’t wait for the ideal conditions to do something (form a relationship, take a job, move to a new place, have a child, remodel your home, go on vacation, write a novel, etc.) or it might not ever happen. While there is wisdom in “look before you leap”, there can also be wisdom in “he who hesitates, is lost.”

The relationships that FFJ has with her common-law husband, Sinclair (who is really a failed actor and kept boy), and her accompanist, Cosme, portray the sycophants we can have in our own lives. It’s always a dilemma for mentors, colleagues, teachers, family members, friends and certainly spouses to face the dilemma of when to be frank with us, for our own good, and when to just let us have our little delusions if they are not harming anyone, anyway. But, sometimes, yes, you really do look fat in those jeans. But should we say that? No one around FFJ (no one on the payroll, at least) has the cruelty (honesty?) to tell FFJ that she can’t sing. And I was left wondering about the moral dilemma that poses; not because they were on the payroll and their “job” was to be complimentary, but when do we have an obligation to be frank with our loved ones, and when do we just let them be?

Jack Canfield, in his book that I like so much and that I use as a primer in my private practice in counseling and coaching for gay men, The Success Principles, says that getting truly honest, helpful, productive, negative feedback can be quite rare. When I do something creative (such as writing my novel, The Boy from Yesterday, or my musical, “PygMALEon”), I always appreciate the frank feedback from a certain close friend who is a brilliant comedic writer and lyricist. And boy, if he doesn’t like something, he’ll tell you. I love him for that. Because I would rather he offer frank criticism in time for me to work on and “fix” something, rather than have the intended audience hate it later. He admits that frank criticism can be tough to hear, but ultimately it’s for the good of the work, and in that it becomes noble.

But for FFJ, people being frank that she has a voice that could shatter glass (and not in the good way) would have been just one more cruelty for a woman already subjected to a number of cruelties in her life. Allowing her to live in her fool’s paradise was not only OK, but in her mind, it was an act of love: “If you love me, you will let me sing here [Carnegie Hall]”, she says to Sinclair at one point.

The “inspirational speech” of the film, which harkens back to the films of Frank Capra and the noble deliveries of Jimmy Stewart, is ironically delivered by one of the comic characters, Agnes, a floozy showgirl (played brilliantly by the 2012 Tony-winning (as Vanda in “Venus in Fur”) Nina Arianda) who confronts the large audience of soldiers at Carnegie Hall who are jeering and mocking FFJ’s performance. With this “cognitive re-framing” from Agnes to appreciate the lady’s efforts (as we shrinks who do Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy would say), the soldiers suddenly see it all from a different point of view, that of the joy of self-abandon and sheer guts, and instead cheer FFJ on with the kind of enthusiasm that wins world wars. Don’t we all wish for that? That an entire group of people would cheer us on, and support and love us, even when we are at our worst?

I try to think of the “take-away” lessons from “FFJ”. Toward the end, Florence has occasion to doubt herself (and haven’t we all) when she says, “They might say I couldn’t sing. But no one can say I didn’t sing.” Bea Arthur, in her one-woman show on tour and on Broadway (“Bea Arthur on Broadway: Just Between Friends”), sings a song at the end called “The Chance to Sing” (Tom Jones-Billy Goldenberg). The lyrics say, “We come, we go. It has always been so…Don’t miss the chance to sing.” This was fitting, because not only were those the last wise words from Bea Arthur in the the show before her encore, but (like FFJ’s Carnegie Hall performance), the show was done not all that long before her death. Bea’s point is well-taken, as was the FFJ approach: We only get one chance in this life. Don’t miss the chance to sing.